Thousands of commoners, of different ages, nationalities and cultures, can identify with Prince Charles. No, not with his royal lifestyle or his promotion of alternative therapies. It's those ears : those unmissable, larger-than-life, wish-I-could-hide-them ears. The facial feature that probably, more than any other, prompted the king-in-waiting, to once whine that he was not as handsome as his princely sibling, Andrew Errant ears come in many shapes, sizes and looks - most of them amenable to the aesthetic surgeon's bag of fixes. Here are the basic defects that make for problem ears and what a skilful scalpel can do for them:

- Protruding Ears

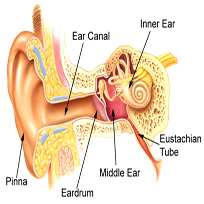

Also descriptively called 'bat ears', these are a common deformity and most often run in families. They are caused by a culprit that ear sculptors call a large conchal bowl. Take your finger from the anti-helical fold and drop it down and back into the bowl. That is the concha (as in conch shell ).

If your concha is too deep and too round, it pushes the whole ear out from the head, increasing the average 15 to 30 degree angle between the head and the back of the ear.

Jibes about protruding ears can begin as early as nursery school, and playground taunts can be psychologically damaging, especially for little boys - little girls have the advantage of being able to disguise their ears with long hair. The distorted self-image that results can carry over into adulthood, even though the taunts may no longer be so brazenly expressed.

Fortunately, bat ears - like lop ears - can be corrected very early in life : between four to six years of age. The surgery, sometimes known by that grisly term, "pinning back " the ears, involves placing permanent stitches in the back of the ears and anchoring them to the head. This pulls the ears flush with the head and obliterates that yawning chasm.

The surgical incisions are ordinarily placed behind the ears, so that scars remain invisible. At times, when external incisions become necessary, they are placed inconspicuously within the normal contours of the ears.

After the incised areas are sewed up with surgical sutures, a dressing is put on and soft cotton padding is used to provide support to the new contours of the cartilage and prevent irregularities in them. A turban-style head dressing protects the ears, and minimizes swelling and discomfort. It stays on for about a week, after which the residual swelling gradually disappears.

The chief source of disappointment in this ear correction arises occasionally from the residual irregularity seen in the cartilage post-surgery. Vis a' vis this, however, it's important to remember that even two 'normal' ears are never perfectly symmetrical. Of course, if there's a marked difference in appearance in the pair of corrected ears, further surgery may be required to improve the result.

The other possible risk in this surgery is the accumulation of blood or fluid between the skin and cartilage, which again can impair the aesthetics of the new look. The cotton padding and the head dressing help to avoid this, and they should therefore not be disturbed.

- Floppy Ears

This inherited condition is also known as lop-ear deformity and it affects the ear's anti-helical fold. To find this structure, put your finger on the curved top of your ear, then run it in a straight line down the flat half-inch of cartilage, until you reach the hard, curving rim that frames the bowl of your ear: That hard rim is the anti-helical fold. Trouble is, in some people the fold has not formed, causing the upper part of the ear to flop down like the ear of a lop-eared rabbit.

To unfurl the ears, the surgeon makes permanent stitches in the upper ear cartilage and ties the stitches, so as to create a fold, and prop the ear up; eventually, scar tissue will form to hold the fold in place.

The surgery can be done at any age, but the ideal time is when children are four, five or six. Not only has the human ear reached adult size by then, but correcting the deformity early protects children from ridicule.

- Ear Lobes

Less-than-perfect Lobes : A third, rather less troubling area is the lowly lobe. Sometimes ear lobes stick out, don't match, or may droop. Enlarged, hanging ear lobes are a common sign of aging. A surgeon can trim excess flesh to make lobes symmetrical or less droopy (an ear-lift, in effect ); a deftly-placed stitch can rein in lobes that stick out.

Torn Ear-lobes : If those sexy, dangle ear-rings have stretched your pierced ear holes into vertical trails, a lunch-hour fix can return them to round. The surgeon uses the same process he'd use for completely torn ear-lobes. That's simply a snip, some stitches and re-piercing. All told, it's a nip and tuck and can spare you from keeping your lobes in hiding.

- Big Ears

These are a rather different story from protruding ears. (Lyndon Johnson had a two-in-one problem - ears that were both, big and protruding ).

Fixing big ears requires a more extensive, rare form of surgery in which the ear is made smaller by cutting away a section in the middle of it. This is surgery that should be carefully considered.

How to tell if your ears are too big? A normal-sized ear is about one-quarter to one-fifth the length of the head, measured from the crown to the chin.

On the whole, ear correction surgery is one of the safest cosmetic procedures. Bleeding is the major, though rare, risk. In 5 to 10% of cases, a stitch will loosen and a re-do may be required. Hence the importance of finding a skilled surgeon.